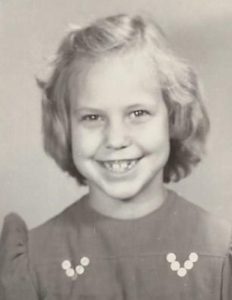

Sand-peppered wind, beckoned when I was about five-years-old. It had a hollow, spirited sound, and I listened. No fear, no questions, just acceptance. Though not a native, West Texas always knew me. Like the wind, playing outside was the best place for me; probably a benefit for my mother too. I didn’t have a lot of toys, but I had a lot of imagination.

Buddy Cobb, my nine-year-old brother, was smart and knew absolutely everything about the world around us. Whenever Buddy and his friend needed someone to be the enemy, they’d let me play war with them; I was three years younger, a girl, and very trusting.

The Korean Police Action happened when I was around six years old. My family listened to radio news reports every evening and unlike me, Buddy probably listened.

Occasionally, Dad treated the family to a drive-in picture show in Lubbock. Cartoons were featured first, then we’d usually see a Ma and Pa Kettle movie, and the final feature was often a war picture. Being the youngest of four children, I usually fell asleep before Pa Kettle whined and scratched his head for the last time. Buddy must have stayed awake for at least part of the last movie, gaining knowledge, strategy, and sound effects from those late-night war shows.

Near the back door of our rented duplex in Shallowater, was something ten times better than a sandbox, a cotton field; better known to us soldiers as . . . a battlefield.

This particular summer we were into digging foxholes. We spent hours chopping holes into some poor-ole-farmer’s crop.

We had wooden rifles and rock hand grenades. When a real airplane would fly over, my nine-year-old brother shouted “japs overhead!” I didn’t know what a jap was, but we’d all dive beneath struggling cotton plants, and cover our heads for protection. According to my brother, they were fierce and something to be feared. Jets flew over daily, because we lived 12 miles from Reese Air Force Base, a pilot training facility, where Dad worked.

Buddy and his friend got to hide in the fox hole; I sheltered in the dirt, beneath a crispy stalk. When Buddy called out, “get up and run Jan,” I’d quickly scoot out from my cover, and take off running down a plowed row. Buddy and his friend chased me, jerking their rifles around like machine-guns, making uh-uh-uh-uh sounds. Sometimes I’d hear a loud “p-shew, p-shew,” behind me, and knew they’d switched to firing rifles. I’d dive between cotton plants, and take off running down a different row. I should add, mother made me wear a dress most of the time.

I heard my brother estimating how many enemy were hiding in the short stalks, and discussing with his friend how to flush them out or ambush them.

It was at that moment, we heard it. All stopped and turned our heads toward the sound. It was shrill, and it was loud. Our mother’s whistle was so piercing, she could burst eardrums, I was sure of that, and she was calling us home.

So, I pretended not to hear her, and continued playing. I even ran further out in the field so I couldn’t hear her at all.

My brother yelled, “Jan! Mama’s whistling for you. You’d better go see what she wants.”

I was mad and grumbled all the way home, “Why do I always have to go in? Mama never makes Buddy come home.”

I heard a third whistle. Not good. Slowly, I put down my grenades, and my borrowed rifle, and grudgingly made my way towards the house.

Dawdling, I inspected familiar cotton stalks, and careless weeds on the way. I broke off a piece of milkweed, stopping to watch the milky substance ooze out the succulent wound.

Out of nowhere, came a deafening growl from an angry sky, even the clouds scattered. In that sweat-faced moment, I froze. Only my lips could move, and whispered, “Japs! Overhead!” I was alone, no grenades, no rifle, halfway between the safety of home, and the secure foxhole, that I’d helped dig. I dove down between two cotton stalks and prayed I wasn’t seen. I laid very still until I could no longer hear the jet roar.

Then, I heard something far more frightening, “Janice Ann, you have two minutes to get in this house!”

I crawled from beneath the cotton stalks, gave a quick sky-scan, then ran home as fast as my legs would carry me.

“Why didn’t you come when I called you?” Mama’s hand swatted my mud-crusted legs.

I wanted to say, “That didn’t hurt!” But, the wiser me answered, “I guess I didn’t hear you.” I lied. I’d heard her whistle, every time. Heck, the whole town of Shallowater heard her. I was surprised that a second swat didn’t follow. Lying to Mama was an egregious offense.

Dust clung to my face, and hair, and clothes, and places it shouldn’t be. Though digging was fun; still, it involved sitting on a pile of dirt. Better things might be imminent, but left to my own druthers, I’d pick the known option, and stay in the dirt. It was familiar, just like beans and cornbread were familiar; and she was calling me in for that? No wonder I dawdled. No thank you.

Mama made me take a bath and wash my hair.

Before long, she stuck her head out the back door and whistled Buddy home.

I gave him a smirk, knowing he too was headed for the tub.

Why did we resist answering her call? Something good almost always awaited. After dinner, beans and cornbread, we were going into the city. We’d usually stop on our way home, at the Bell Dairy in Lubbock, and get ice cream. I got strawberry, and for 15 years, never tried another flavor. You can’t improve perfection.

So, what’s my point? I learned to wallow, at a very young age. Though I don’t dig in dirt any more, there’s other icky stuff to wallow in, you just can’t see it. Things like insecurity, fear of rejection, fear of sickness, what if I’m not good enough at writing, you know. Dumb stuff. And left to my own druthers, I tend to hang there. Then sometimes, way off in the distance, I’ll hear a shrill whistle, calling me out of my wallow to focus on what’s good in my life, and there is so much good.

So, I rise up, shake away my druthers to uncover a face the world recognizes, and move away from my wallow.

Today, I’m a North Texas resident with sand in my craw. And every spring when the wind howls, I imagine it’s West Texas blustering, to remind me of home. To tell the truth, I never totally gave up playing in the dirt. Now, I fill numerous pots with potting soil, and flowers. However, the biggest and best cask is filled last, reserved for something special . . . cotton seeds.